I recently came across an article (1) which discusses the magnitude of dropouts from elite schools in India over the past 5 years. This was data from the response of a minister to a query raised in parliament. As with everything, I have seen some takes on twitter which inevitably are on lines of “the cause for this is something which I don’t like, and the solution is doing something which I do like”. In this write up, I will attempt to analyse and offer a suggestion which I think mitigates the problem.

Some disclaimers first.

· Of course, no solution will ever be a panacea for all problems, and inevitably, the course of action will be and should be driven by the priorities, ease of implementation and associated trade-offs.

· Also, such discussions can go into tangential paths. My sparring partner usually bests me in debates with the logic - “if that is the issue you want to raise on this topic, then it should have been a separate agenda item”. As much as I hate this line of thinking, especially in topics which have inter-linkages, it does offer clarity, brevity and more importantly, eliminates whataboutery. So, I will try to stick to the “agenda item” as much as possible, without delving into related topics like the merit of affirmative action itself.

· Finally, every opinion is biased, even if it is presented otherwise. An argument always has some axioms behind it, most of the times hidden and unknown. A good reader can typically decipher the underlying axioms and identify the information value of the argument. Therefore, you can now adjust for my biases, to discount or amplify certain points I might or mightn’t make. For the record, my biases are:

o I am pro affirmative action

o I think an IIT/IIM seat is both a leg up to better life and has overrated halo

o Most folks are good in nature, but bounded rationality brings in sub-optimal outcomes (Nash equilibrium style) and leads to real world pathos

o Primary education is the single biggest failure of India since independence, and it continues to be so, and

o My personal experiences

With the disclaimers out of the way I would like to analyse the problem by trying to understand various issues mentioned below and then propose a solution

· Has the distribution of student quality changed over time?

· What are the dialectics in higher education institutions?

· How has pedagogy changed over the same period?

· What could be the reasons for the dropouts?

· If there must be changes, what should be the objective of higher education to optimise for?

· What tactical solutions offer the maximum impact given the current situation?

· What is the long-term solution if any?

Has the incoming student distribution changed over time?

The class cohort profile could have changed significantly over time due to the following factors.

· changes in the filtration process over time, i.e., entrance examination

· changes in aspirant profile over time

· other exogenous factors

One of my mathematics teachers from school used to comment about the quality of students he had seen over time. He would say that while best student of his class has only become better with time, the average student has only gotten worse. It was an interesting statistical observation as it covers both cross section and time series. As a kid, I was puzzled by this observation. But as an adult, it is not surprising given how certain real world distributions work. It also is a function of the society and its economic and cultural systems, where in the spectrum of maxi-max to maxi-min do these systems lie. The reason why I bring up this anecdote is to say that there is basis to explore the hypothesis that the cohort of students has changed significantly over time.

Let us see how the filters for the colleges have evolved over time. I will take a single example, JEE for instance for sake of argument. There are two vectors for selection in these entrance tests – difficulty of the exam and the number of aspirants one is competing against. While the difficulty of exam has probably been increasing incrementally, it has a limit, bound by the knowledge an average seventeen-year-old can possess. In contrast, competition has grown manifold. When I was younger the awareness of JEE was so limited that going out of state for engineering education was in general considered an outcome of getting a very low rank in state engineering entrance exams. But this is no longer the case. In 2015, 14L aspirants took the exam (2). This number has fallen to 8.5L in 2022 partly due to reduced re-attempts (3). But this is still significantly higher than 1978 where 30K took the test (4) (I am assuming JEE Mains equivalence with JEE exam of the past, since there was a single test at that point of time). As the aspirant count increased, the need to change the format has become necessary to process the volumes. MCQ format brings with it greater variance in student cohort which comes in as compared to traditional subjective exams. MCQ format is also a more popular testing mode compared to subjective exams. Thus, this switch has made the exams more accessible to a wider set of aspirants as well.

Twenty-five years ago, there were 6 IITs and IIMs. The number of seats were also significantly lower, and there was a sampling bias in terms of those who attempted for these examinations. Till 1974 English was part of the JEE exam, at a time where literacy in India was in mid-thirties, forget English literacy. Even now it is limited to English and Hindi. It has been a long-standing demand of many states to have JEE conducted in regional languages. Thus, the background of an IIT graduate in 1974 is likely to be urban from a well-established family whereas that guess will be wide off the mark right now simply because of change in aspirant profile.

While SC/ST reservation has been there for a while, it has been expanded to include the OBC (NCL), EWS, PWD and Women (supernumerary). Empirically, affirmative actions bring in additional variance into the incoming student pool. I have taken example of 2022 marks by rank table to illustrate this. This should be taken with a pinch of salt as marks and grades don’t show high correlation especially at lower ranks where a single mark can move one’s rank by a few hundred. The last line of the table also shows the equivalent rank of last score in common rank list. Most of the arguments against affirmative action obviously focus on this disparity presented in above table which doesn’t show the women specific supernumerary data. But again, that is a separate agenda topic. What the table does show is there is sufficient evidence of heterogeneity.

To summarise, there appears to be a significant divergence of student mean and variance (allowing myself a statistics pun) over the last forty years. This change in distribution has some implications as I would discuss further on.

What are the dialectics in higher educational institutions?

There are different stakeholders in the educational institutes. While the students and the faculty do appear to be the primary stakeholders, we have the industry, government and family of students who are secondary stakeholders but influential, nevertheless. On one hand students and family might argue that the objective of an institution is to ensure the students land a job, whereas the industry players might say it is to ensure the students should have requisite skills for a job. While both requirements appear similar, the implied requirements are very different. For the top tier institutions, the selection process is such a strict filter that employers will hire them even if the institute doesn’t teach them well. That will not be the case for a second or third tier college whose edge is teaching those skills. An example of this would be that while an IIT would never teach a programming language as a course outside its introduction in first year, local engineering colleges would focus on multiple language course like C/C++/Java in early noughties.

The IIT professors might indicate that their goal is to ensure students are geared up for research and critical thinking. The government has very orthogonal expectations like social justice, development of ecosystems, long term benefits in research etc. Thus, there is quite a dissonance within the system about its stated objectives. None of them are wrong, but it should be recognised that they might be at odds with each other at times.

The students’ and their families’ bias for jobs is reflected in the fact that placements and not the interest of student are the driving factor in the branch and college choices. At the same time, it is widely agreed that industry finds much of the output of current higher education system near unemployable (5). While this might be less applicable to the top tier institutions, it is a serious problem as one goes down the college rankings.

Another unrecognised tension is between teaching and research. The students and industry would like the professors to teach the necessary skills for the job. But government looks at the top institutions as research places and it is reflected in UGC criteria for professors. Research in general and publications in particular carries a significant weightage in promotion requirements. Based on the comments by ministers in newspapers, it is also clear that government has an eye on the world rankings and research forms a big component there as well. The proliferation of C/D grade journals in India whose only job is facilitate a publication upon payment is proof for this.

The last actor left unsaid is the owner of the education institution, which in the case of institutes of concern is government. But the number of private owned educational institutions is significant in the country. Thus, their objectives are important to note as well. But the less said about most of these education societies, the better. Many of them are a façade for corruption and a haven for money laundering. The proof is the number of politicians who run educational institutions. But this point is more a passing lament and not a topic for further discussion either.

Has pedagogy changed over the same period?

The reason why we discussed the opposing forces in previous section is to bring in contrast with how it would have been four decades ago. Again, we will focus on engineering for sake of argument. If we take 1970s as the base case, we had a small pool of professors and students. The opportunity set in the country was unfortunately limited, and at the same time, need for knowledge was much greater as well. This meant that a substantial portion of graduates emigrated abroad for either better opportunities or for further studies. It also meant that there was much greater alignment of interests between professors and students as compared to now around doing research, and the students themselves were more homogeneous actors.

But teaching and research are very orthogonal skills. A professor joins a college after finishing her PhD and with a couple of years of post-doc experience. At the university interviews, she is expected to present her teaching and research statements. The university checks for alignment of interests there and then appoints the person on probation before confirming few years later. This individual would have typically spent most of the past decade focusing on research. They would have assisted a professor in grading, setting exam papers, held recitation classes, given a few classes, and co-taught a course at the very best in those years. The point I am trying to make is they are researchers first and teachers next. This is in contrast to a school teacher, who in her B.Ed spends most of the time on pedagogical methods. A school is a place where the student heterogeneity is greatest, and the B. Ed curriculum aims to address that (in theory at least).

A good teacher should take the whole class along, should understand why a student needs her course and what would be its value in future. The utility could be different for a student who aims to get a job as compared to a student who seeks go for further studies. They should recognise that they are not teaching just for the front benches (though interactions with them offer the greatest job satisfaction), but at least for the middle benches. An ideal teacher will ensure the worst student has the basic knowledge necessary from her course, the middle student is above average in terms of employability, and the academically inclined kids have been provided with both the resources and passion that would set them off on their quest for further knowledge. This is a tough gig and the job description hasn’t really changed from ancient Indian Gurus who had their gurukulas Gurus or the Victorian age school-teachers, who would essentially teach different grades/ages varied subjects simultaneously. Thus, an ideal teacher is very much worthy of the phrase – acharya devo bhavah.

Now a professor at one of the elite institutes typically has a tenure of 35-40 years, joining in late twenties and retiring at around sixty-five. The reason why I mention this point is to give a context that the oldest professors have probably taught a small class in eighties that was homogeneous in nature now has to teach a class that is five to ten times larger and has much greater heterogeneity. The heterogeneity is not just in backgrounds of the students but also in their aspirations. It is now to question how the objectives that a professor has for a course changed with evolution of time. Most good professors usually update the material for the latest developments in technology. But do they update the course objectives for the change in environmental factors?

Pedagogy has two aspects – one is the instructions a student has received which would be aimed at achieving the objectives for the student from a course that the professor desires, and second is evaluation of the student against the supposed objectives. So let us talk about the grading system which also has been same over the past four decades. Not only do we have a system where students make choices which are often misaligned with their interests, the evaluation system makes that a double whammy. Unfortunately, this is a universal phenomenon. Countries in the west have recognised the challenges in standardised, monolithic testing, but their solutions are worse than original problem which are essentially an implementation of minimising the maximum. As a result of various committee proposal and current National Education Policy, the number of credits a student has do for his under grad has come down significantly, with various liberal arts courses added as well. But again, those don’t necessarily address the problems which come with the current grading system.

What could be the reason for dropouts?

The primary lines of thought that I have seen on social media/media are on the lines of either (i) there is caste-based discrimination at the educational institutes or (ii) affirmative action students are undeserving students of the seats in such places, and they are unable to withstand the pressures of education because of that. Most other arguments are a variant of these two points. I thought these arguments do a disservice to a complex topic by reducing it to binary. As I mentioned earlier, I don’t want to address the reservation and associated problems in this note. I can only summarise my thoughts as pro affirmative action but left to me, current affirmative action system would be tweaked a fair bit which seems to focus on headline numbers and less about ensuring the benefits are long lasting and equitable. There has been significant expansion of seats over the last two decades due to addition of seats through reservations and addition of new institutes. I submit that this process along with affirmative action only addressed the first order effects of a country with growing population and ignore the second and third order which are equally important if not more. By this I mean, both the quality of the education process, as well as quality of output.

My core contention is that the major reason for dropouts at the top educational institutions is the terrible process of grading. The current system in India (and across the world) doesn’t allow people with different speeds to study together, forget different skills. It is a rigid, time bound process that one can argue is loaded in favour of the education institutions to maximise their objectives. Due to this nature, we have a system where there are no buffers for failure. The expectations of joining a top institution in the country are huge. On one hand you have professors who are not exactly teaching specialists. They also have expectations of their students which are very different from the student’s own objectives. The teaching is biased in a way to develop skills in students as if they all want to go for specialisation studies. Compared to 20 years ago, the number of students who are applying for higher education abroad has dropped sharply. I am glad for it since it’s a reflection of a country which is growing and has tremendous opportunities. The flipside of this coin is that employment headlines in media create unnecessary pressure which I think is ill understood by academia. The professors do feel aggrieved (and justifiably so) that most students have no interest in studies except for jobs (and fun).

But that is a harsh reality induced by the change of profile of students who enter the campus. This is no longer the same cohort which entered 30-40 years ago. This is the result of the tension in objectives we discussed earlier. In a normal negotiation between equals, there is a compromise. But here there is power asymmetry favouring the institute. While the system recognises this power asymmetry and has been working hard to make it better for students, the unfortunate fact is that exogenous factors are counteracting the impact of these changes at a much faster rate. The case in point is the number of students who are currently on rolls and staying beyond four years (or 5 years) to complete backlogs.

A 6/4 (6th year students for a course to completed in 4 years) were rare in our days. Now a days it is not that uncommon, and I have heard cases of 9/4 as well. I claim this reflects a system of poor evaluation which has not adjusted for the fact that selection process has changed. Many of my friends teach at these institutes and they empathise with students on this point. One of the best suggestions I heard was from a professor who said that (s)he likes to declare upfront to students on what they need to do to clear the course as (s)he thinks the biggest fear amongst a large set of students is just that – failing the course.

In my small class at my undergrad, I have classmates one of whom I am hoping will go on to win a Nobel, another who will get a Turing/Fields medal. But I have also lost two of them to suicides and couple more who suffered from depression, and either left the course or suffered significantly during the course. I joined my college two weeks late as I was bedridden at the time of admissions. For all practical purposes, I was out of action for the first month. The speed at which courses went in first semester meant that I was probably in the bottom third. But thankfully, I wasn’t stressed for two reasons – I knew my father had my back as he always told me to dropout if I felt uncomfortable and secondly, my passion was always finance. The point I want to emphasize is that grades are Martingale processes at these places.

Mental health is a serious challenge. My class size was 30. It was hard for any professor to keep tab on what the students are going through then. Now the class sizes are 5x larger. It would be difficult for a professor to remember the name of a student leave alone trying to understand their mental health situation. It is not for lack of trying, but the ones who need it most are the ones who are unlikely to respond to any outreaches. No matter how many top-down policies are enforced, the only protection a student has in this matter is his family and company. Unfortunately, family which has been the backbone support till 12th no longer is available and that is where the trouble starts. Undergrad is that awkward age where one is not yet an adult, but the world expects them to behave like one. Friendship is also a lottery ticket due to the above said martingale nature of grades.

No student enters the institute wanting to fail. Low performance often creates enough of internal apprehensions of belonging to a place. A dear friend whose loss still hurts me till day was an Olympiad medallist but who had a lull in his research. His groupmate was the other friend who I would classify as a prodigy. The source of apparent under performance doesn’t matter at this point. For those who have come in through affirmative action, it would be attributed to that; for those who have come from “factories” it would be factory learning and no real aptitude (In 2008, director of IIT Madras mentioned that coaching institutes are allowing less than best to come to IITs); and for women, their gender. I know we would like blanket answers like discrimination, misfits etc but in my experience the answers are much more complex than that.

If there must be changes, what should be the objective that higher education should optimise for?

I would like to pose the question of what the objective of Indian higher education system should be. I like MIT’s mission objective – “to advance knowledge and educate students in science, technology and other areas of scholarship that will best serve the nation and the world”. For example, every one of our colleges being great research places is a fantastic objective if not for the fact that we are an economy who per capita income is not even 2000 USD. There should be greater emphasis on teaching.

Teaching is an art that is also specific to the domain, and audience. My child indicated to me that I am ill equipped to teach her whereas my investors do think I can explain a complex strategy well. A friend of mine whose opinion I respect convinced me with his line of thinking that it is not the job of a professor at a top tier institute to teach since they are research centric, but it is job of a student to learn. While I did agree with that opinion 20 years ago, I don’t agree with it anymore. The answer is much more complicated. I see that students do need help on this side, especially the undergrads.

For good or bad, I think the market forces tend to be good judges. Given our current situation, the emphasis of everyone in the education system should be employability of students. This has the quickest return on investment for everyone in the ecosystem. The business schools do get that point. The lower tier engineering colleges do also get this point. Unfortunately, despite the expansion of seats and places, the mid and higher tier colleges seem to have missed this development. This is further reinforced by ministry of education directives to faculty. There is a Telugu idiom which goes thus – ‘to become a tiger, a fox put hot branding rods on its skin to get the black stripes’. We are doing exactly that. We are a developing country whose primary goal should be to elevate the average skills of the population. Thus, we need more teachers – preferably those who have industry experience but at the very least who understand that their job is to make their students employable. This is not specific to elite institutions but across the board.

The students would appreciate that and left to forces even markets would. It is not surprising that the highest paid teachers in India are those who coach competitive exam aspirants. The fact that most of the hiring companies conduct their own exams to filter out students for interviews and don’t consider the grades of colleges (even IITs) at undergraduate level is an indictment of institutions being out of touch with reality. Putting student’s preferences first aligns the output with the ecosystem and I submit that, in long run, academia will also benefit from this as their efficiency improves.

What tactical solutions offer the maximum impact given the current situation?

An ideal system removes the halo the elite institutions have. This means that cost of not clearing a competitive exam should be an acceptable outcome to the aspirants. This happens when the next tier institutions offer comparable quality education and there is not a dramatic shrinkage in opportunity set. Thus, there are two problems in the current scenario. The first one is to enable different paced evaluation. Second is to create a system of consistency in quality of education imparted.

The government has been addressing this problem of pressure on students at school level in terms of pruning of syllabus. The thought is good, but approach again ignores the second and third order effects. One can see in California how removing algebra has only pushed students toward tuition for those who felt they will need it, and is exacerbating gaps. This is an outcome of an inflexible system. Another approach used in places like Singapore is homogenization. Kids are calibrated by skill and sorted into sections. I find that approach unsuitable for a variety of reasons and it doesn’t work for us here where the whole point of affirmative action is to break elitism.

I think there could be a different solution. Any subject/course to be taught should ideally have two parts – first is fundamental that is a perquisite for clearing that course/subject and second is advanced. The material could be split 50/50 but for evaluations the weightage could be 75/25. May be there could be two classes of basic followed by two classes of advanced and since advanced is not mandatory, those who are aiming for basic could use that time to reinforce their fundamentals. In fact, these days there could be recitation classes by Teaching Assistants if needed. This recognises the diversity of students and gives them tools to choose their path of success. This would require a one-time effort from the side of faculty to refactor courses this way.

This could also be applicable for schools. Don’t reduce the chapters in the subjects but break the chapters into material for evaluation and interest. Those are who are interested can read and practice the advanced material. Having both fundamental and additional content in the same place allows students to be aware even while not being coerced to study it.

I would think a system where there are two paths to graduation – one with completion of courses with no grading but only pass/fail and second with grading - would solve this. One could call it a degree and other a degree with honours. A pass/fail grading is very suitable for a system where one is trying to maximise the minimum performance. There could even have separate papers for these categories. It will take a little more effort from faculty, but I think it will have huge positive effects on both the dropout number and quality of students graduating. To reduce the possibility of stratification and stigma, those who go for honours and fail to achieve beyond a certain cut off (75%) should also be given a regular degree. As discussed earlier, the value of CGPA is diminished greatly if the recruiter conducts her own exam to select candidates for interview. By focusing on P/F grading, I believe the average quality will increase overtime if the material in fundamental part of the course is relevant for employment.

Now comes the second point which is to improve the consistency in quality of education imparted. It is a subjective opinion, but most of the research output is nonsensical. I am not even talking about those research papers where the author doesn’t understand the statistical tools they use. A research eco-system has the same profile as VC investing. One needs to be ok with 99 duds for that 1 moon shot. The only problem is VC investing is risky and thus limited to accredited investors. Index investing is more appropriate for someone with lower net worth as risk function is different. A different approach would be to allocate say 10% of corpus for risky investing and keep 90% in regular stuff. This approach would work very well for us.

We need to declare few institutions to be research focused institutions and rest should be teaching centric institutions. Ideally the research focused institutions would only teach post grad courses and above. Left to me, I would go to top IITs/IIMs and ask the institutes for the professors with best teaching scores and then ask them to design course material and lectures. These should go on NPTEL. NPTEL is a criminally under used resource in our country right now., more so given the standard of teaching in colleges especially at the lower tiers. I would also argue that research should not be an incentive for most of the faculty in the country. Instead, it should also be mandatory for them to have cleared the NPTEL exam for the course they plan to teach in the past two years. This would bring in consistency in quality of education being imparted.

What is the long-term solution if any?

Birth is biggest lottery we get to participate in. Most of the final outcomes are variations around that mean. As a society, we have got our affirmative actions messed up in focusing on end distribution and not the process. The best place to eradicate this lottery of birth starts with childcare systems. Next best place is primary and secondary education. We are in the mess we are right now since our governments have not placed enough emphasis on school education. If our quality of school education were much better, the output at the tenth and twelfth grades would be much more equally distributed across various categories. The quality of a country depends on the quality of schooling. A tiered approach based on ability will be easily absorbed and society can be meritocratic if everyone believes that they will get equal opportunities and lottery of birth is mitigated to a certain extent.

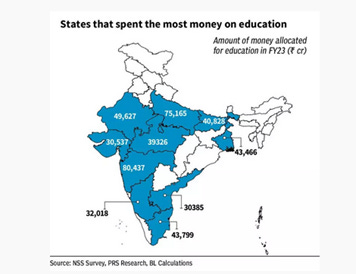

It is not that the governments don’t spend money on education. Below is an infographic on the state expenditure on education (6). Taking the example of Maharastra which has nearly 6 mio of its 20 mio students in government schools(7,8). Even if I assume that number to be 10 mio, that will mean an annual budget of 80,000 INR per student. We do have to adjust some of that for subsidies for residential welfare of tribals and operational challenges of running schools in remote areas etc. Still the budget per student is significantly higher than an average private school fees per annum. I am confident that analysis of the expenditure of other states will lead to similar conclusions. But the quality of output doesn’t seem to reflect this expenditure. The question is why. The answer from my anecdotal experience (generalising from my native state’s knowledge) is corruption. Government teachers get paid approximately 50,000 INR per month, and this makes it a very good dole out prospect.

Ironically, a line of thought (9) argues that India should be investing in post primary education as return on education is lower for India than what should be for a lower- and middle-income country and return on secondary education expense is measly 2 percent. I believe the reason is quality challenge as described above.

Our education system is a mess at every level. At the top the pie is so small that we have dog fights to get into a system where the value add is from the selection process rather than education imparted, and the opportunity cost of not getting into that selection is high. While the governments of past and present have taken several steps in reducing opportunity costs via expansion of institutions, seats and added diversity through affirmative actions, the education process has not reacted to this. This unfortunately leads to reinforcement of stereotypes and leads to precious resources being wasted as students drop out. The source of our current problems remains school education and we are suffering for the sins of our past where we over allocated resources to higher education instead of primary and secondary education.

In terms of higher education system, it is imperative we need to solve two problems urgently. First is to reduce the dropouts at the elite institutes and second is to make education market more helpful for employment generation. Switching to PFH (Pass/Fail or Honours) mode of evaluation should help everywhere and similarly, removing the emphasis on research in evaluation of professors. Imposing requirements like needing to clear an NPTEL course on the subject (s)he is going to teach would offer more tangible benefits to Indian skilled labour markets over time.

Sources and References

3) https://nta.ac.in/Download/Notice/Notice_20220711113052.pdf

4) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joint_Entrance_Examination_%E2%80%93_Advanced

5) https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-04-17/india-s-worthless-college-degrees-undercut-world-s-fastest-growing-major-economy

6)

https://currentaffairs.adda247.com

7) https://censusindia.gov.in/census.website/data/data-visualizations/Age-Gender-Ratio_Pyramid-Chart

8) https://mahasdb.maharashtra.gov.in/index.do

9) https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/the-curious-case-of-investment-in-education/articleshow/80306498.cms?from=mdr

I found your analysis of the blog post to be really insightful, and I particularly resonated with your suggestion to split courses into Core and Advanced components. This approach offers several benefits that are similar to an elective system, where students can opt for the Advanced part of a course based on their interests, aptitudes, and desired specializations.

By doing this, students have more freedom to pursue what they are passionate about, which can reduce undue stress and anxiety associated with taking on too many courses simultaneously. This can also improve students' mental health and well-being, as they are not overwhelmed with a heavy course load.

Moreover, the Advanced component of a course could be designed to teach practical skills that students might need when they enter the workforce. Some of these could be offered as self-study options through pre-recorded video series, which would reduce the burden on faculty to cater to a wide range of electives via live classes.

It would be a great idea to offer these electives in partnership with potential employers, who may have a vested interest in identifying potential candidates early on. These could take the form of mini-internships, where students gain a glimpse into the real-life applications of the subject matter they are studying.

Another suggestion I want to add is to establish a system of buddy/mentors for new students joining the institute, with 3rd/4th-year undergrads continuing the relationship even after college until the first year finishes their education. Although this idea is in place in some form or another at many institutes, it may not be receiving the attention it deserves as a measure to ensure mental well-being, reduce dropouts, and provide support to students during a phase when they are away from their families (who filled this void during pre-university days).

Most students are unaware of the career options available to them and the life that awaits them after college. They need guidance on the kind of resilience they need to build to be successful in life. If institutes track the benefits of such mentorship programs and continuously work to improve them, it could pave the way for a much better community.

With rising life-expectancy and a consequential rise in age of retirement, it might be interesting to explore the prospect of increasing the duration of university life perhaps, turning the courses from 4/5 years to 5/6 years, without adding additional course content. burden

Overall, your suggestions offer valuable insights into how institutions can improve their academic programs and support students' well-being.

Baal, really nice post. You’ve discussed so many important things here. Apart from improving schools and colleges from a learning perspective, I wonder if we must also think about investing in mental health and other support systems, especially when their families aren’t around or informed enough to support children mentally. In fact, I believe government health departments actually have budgets allocated for this purpose, at least at the school level, really not sure how much of this ends up getting utilised and how though.